Reading What My Bones Know: Reflections and Guidance for CPTSD

LISTEN OR READ

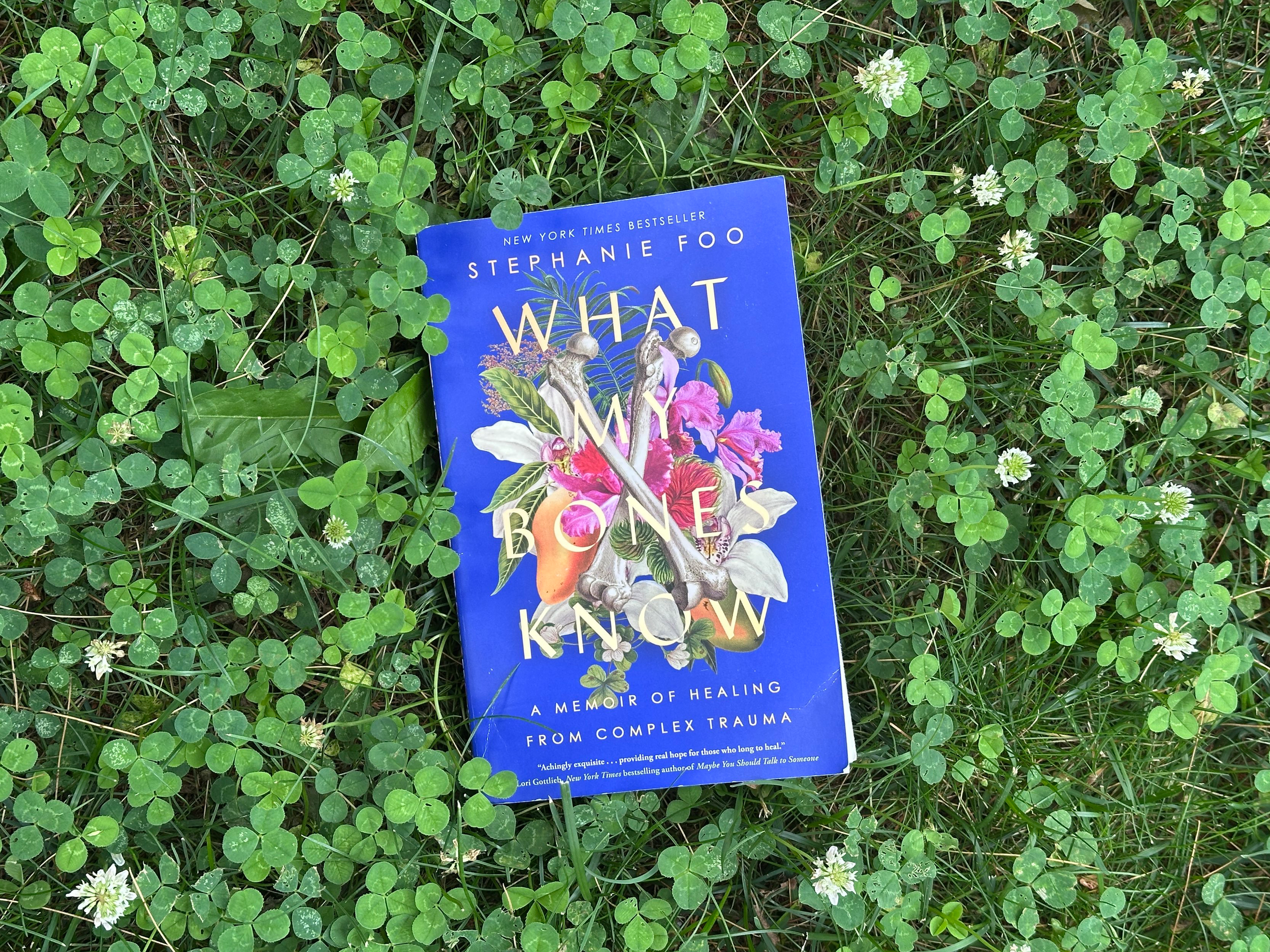

Initially, the cover attracted me—I picked up Stephanie Foo’s memoir What My Bones Know from a large bookstore display because the illustrated cover is beautiful. Published in early 2022, I put it back down because its topic—healing from complex trauma—is my work life. I’ve eyed it in many bookstores and finally picked it up from Octopus Books in downtown Ottawa with a sense of acceptance. I think I knew I was going to read this book, but I had to wait until I was ready. I gave myself the grace not to only read books on trauma, trusting I would get around to it eventually.

(Having a Master’s in English helps here—you learn to accept that you’ll simply never read everything. And yet, when people learn you studied literature, they inevitably ask about their favourite or most important reads you haven’t read. Acknowledging and accepting this early is key to not drowning in imposter syndrome.)

While a deeply personal and researched memoir of one woman’s journey through healing complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD), I found Stephanie Foo’s writing both luminous and incisive. She depicts memories, events, and places so the reader really feels them—though we’re around the same age, so her Jimmy Eat World references might have landed more clearly for me than for others. She never belabours any scene. The writing is so well-honed I was surprised to find myself at the end of Part One; it didn’t feel incomplete at all. She delivered a thorough depiction of the horrors of her childhood and brought her readers closer to the present with an efficiency that never felt disrespectful to the content.

Foo’s book is an honest, deeply personal account of trauma, survival, and the search for understanding and healing from abuse by one’s parents, and the complexity of that legacy. But reading a book like this is not always simple. As much as I recommend reading it, I also want to share some reflections and gentle guidance for approaching it with care.

Your Suffering Can Also Be Real

What My Bones Know details Foo’s survival of physical and emotional abuse and abandonment by her parents, tracing a cross-continental story of intergenerational trauma, racial and cultural experience among the Asian diaspora in California, and her determined, often painful journey toward healing through mind-body work, multiple therapists, and even severing ties with parents who—despite her compassion for their histories—refuse to take accountability for the abuse they inflicted.

Even reading that sentence could plant the tiniest perception that Foo’s trauma is “real trauma” and yours isn’t. Foo references the “Oppression Olympics”—the comparison and overt effort to suggest one’s trauma is more harmful or real than someone else’s—while also acknowledging its ultimate futility. She writes about a support group for other CPTSD survivors and how the sharing of trauma stories can actually provoke us to minimize our own experience.

Foo even fronts the book with an Author’s Note ending, “I won’t judge you if, at any point, you need to skip ahead a few pages. And I’d like to promise you this, even if it is a bit of a spoiler: this book has a happy ending.”

Remember: healing from CPTSD isn’t contingent on your suffering being comparable to anyone else’s. It’s about acknowledging the impact of chronic, relational, or developmental trauma on your nervous system, sense of self, and relationships. Diminishing your suffering moves you further from accepting the impact of your own experience.

Let’s agree: I can honour my experience while learning about others’.

One Path Made of Many

Foo is a radio producer, journalist, and author, and her time at This American Life is depicted in the book—highlighting the over-performance born of her trauma as well as the re-triggering of it by an abusive boss. She brings her thorough research skills to her writing as well as to her personal healing. For example, she weaves colonial history in Malaysia into trauma’s effects on epigenetics, alongside how restorative yoga became one of the modalities she found supportive.

At times, Foo’s memoir reads like a relentless quest—and frankly, I felt proud of her for acknowledging the letdown, despair, frustration, and anger she experienced when a therapy or therapist fell short, as well as her perpetual reinvigoration and commitment to trying again.

This could feel overwhelming. She outlines many therapies and healing modalities. But I appreciate and recognize the clinical truth that healing isn’t a linear progression through obvious therapies. Some modalities won’t work for you now or ever (but they might one day). You don’t have to do everything at once. Healing deepens as readiness, support, and understanding grow.

A client once said to me, “I’ve achieved more in three sessions with you than I did in ten years of therapy.” While I appreciate the expression of relief and gratitude, I also know those ten years of effort got them to the moment where our sessions could be so effective. (And I hold the awareness that for some people, I might be Foo’s “Mr. Sweater Vest”—not the right therapist.)

What My Bones Know doesn’t depict healing as straightforward or easy, but it certainly uplifts its possibility.

Validation Can Also Be Difficult

Foo writes with welcome frankness about the toll of trauma on the body, including her experience with PMDD (premenstrual dysphoric disorder), which many of my trauma clients also experience. Many trauma survivors struggle with conditions they didn’t realize were linked: chronic pain, autoimmune disorders, severe premenstrual symptoms, even traumatic brain injuries.

When I made the connection between PMDD and CPTSD for one of my clients, her reaction roved through validation, grief (“this makes it so real”), and anger. Validation that your suffering is real isn’t inherently or immediately relieving.

Consider reading with compassion for your own body—and include your body in the experience of reading. Ask: What do I notice in my body as I read this? If you sense dissociation creeping up, that’s good data. Ask: What might my mind be trying to protect me from? Can I offer myself care here?

A Few Notes on Race, Culture, and CPTSD

Foo writes openly about the racism and cultural expectations she faced as a Southeast Asian American woman, including the “ideal immigrant” narrative that blinded her high-school teachers to rampant abuse in her community among well-off Asian families. (Spoiler: there is a social worker at her former high school who eventually sees and validates her experience.)

Cultural, racial, and intergenerational trauma shape the wounds we carry and the ways we seek to heal. What is meaningful to Foo may not be meaningful to you, but her sharing is not just informative and inspiring—it was a meaning-making exercise for her, too. That can be a critical component of your healing.

You might ask: How has my own cultural or family context shaped my experience of safety, belonging, and identity? How has it minimized or distorted what happened to me—and to the generations before me?

Foo describes how generations of her female Chinese-Malaysian ancestors struggled to survive and care for family. She highlights the Chinese word 忍 (rěn)—endurance evoked by a knife over the heart—and how generations were taught to “eat bitterness,” holding their pain in silence like a blade lodged in the chest.

In my practice, I see this pattern in many forms—across cultures, it often shows up as a mandate to minimize suffering and “just cope” at great personal cost. While my own white, privileged British family may bear little resemblance to Foo’s upbringing, we still have so much trauma in our family tree that was similarly explained away as “unfortunate” or minimized with, “Well, that’s just what you did.”

Bibliotherapy

Reading What My Bones Know can feel like listening to an interesting, well-read friend share the unvarnished truth about what it means to live with complex trauma. It’s not a manual—it’s a testimony to the incredible resilience demonstrated by so many who have lived through so much.

If you choose to read it, do so with kindness for yourself. And if it stirs things that feel too big to hold alone, consider bringing them to therapy. Healing doesn’t have to be solitary.